In this article I will try to give a general overview on Francesco Ferdinando Alfieri’s treatise (1653), in order to explain what it contains, how is it useful for spadone hemaists and what are its limits. Alfieri is absolutely not as trendy as Godinho or Figueyredo, but let’s find out more about him.

Alfieri and Italian spadone retrospective

We usually hear about Alfieri as one of the prominent fencing authors who has written about this topic. In fact, he is the only Italian master who has left us enough material to build a consistent bridge between the Iberian montante tradition and the Italian spadone (that, if you had doubts, in my opinion are actually the same weapon, but this topic and its historical evidence are matter for a future article).

Somehow Alfieri is for Italians what Figueyredo is for the Iberians – mostly because they both decided to approach this weapon techniques during the same decade – although the latter has provided us with more valuable sources, as we are going to discover.

Fact: we haven’t found any earlier Italian Renaissance fencing source that provides us specific techniques for a multiple fight in the way Iberians do. Giovan Antonio Lovino (1580), Giacomo di Grassi (1570), Marc’Antonio Pagano (1553), Camillo Agrippa (1553) and Achille Marozzo (1536) focus all on the duel-like one against one matter (I know, Marozzo talks about spada da due mane, but this will be another article too); something that has little or nothing in common with the Iberian montante tradition of the so called Esgrima Vulgar approach of regras and multiple fight. Di Grassi and Agrippa, along with many other little excerpts that you can read among The Spadone Project Facebook posts, help us reconstruct – by short sentences and hints – what was the approach to this sword on the battlefield and in military context across XVI century, before its slow disappearance, but there is no real corpus of Italian structured rules a la Spaniard. Until Alfieri.

Alfieri’s treatise on spadone: what does it contain?

Alfieri divides his treatise in 21 chapters: the first six chapters expose a general introduction to the weapon, providing useful and clear tips and teachings about the stepping, the size of the weapon, the way of carrying it and the way to face the enemy correctly; perhaps you haven’t read it, but if you are familiar with big two handed swords practice, probably you already know part of these notions: there is nothing really special inside these chapters but all these obvious little tips helped us shaping what we know today about spadone so, thank you Francesco. He is the one who states that during that time spadone had no legal prohibition and that was common in many provinces, allowed by every Prince and carried in many ways at the owner will. A statement strange to believe, if we consider some Italian weapons regulations (Venice and Florence), ancient opinions (Pomponio Torelli) and the general lack of written evidence compared to all those referring to XVI century, although we should trust him…

The following fourteen chapters describe fighting techniques and drills; the last one is just the author closing words of no particular interest from a fencing point of view.

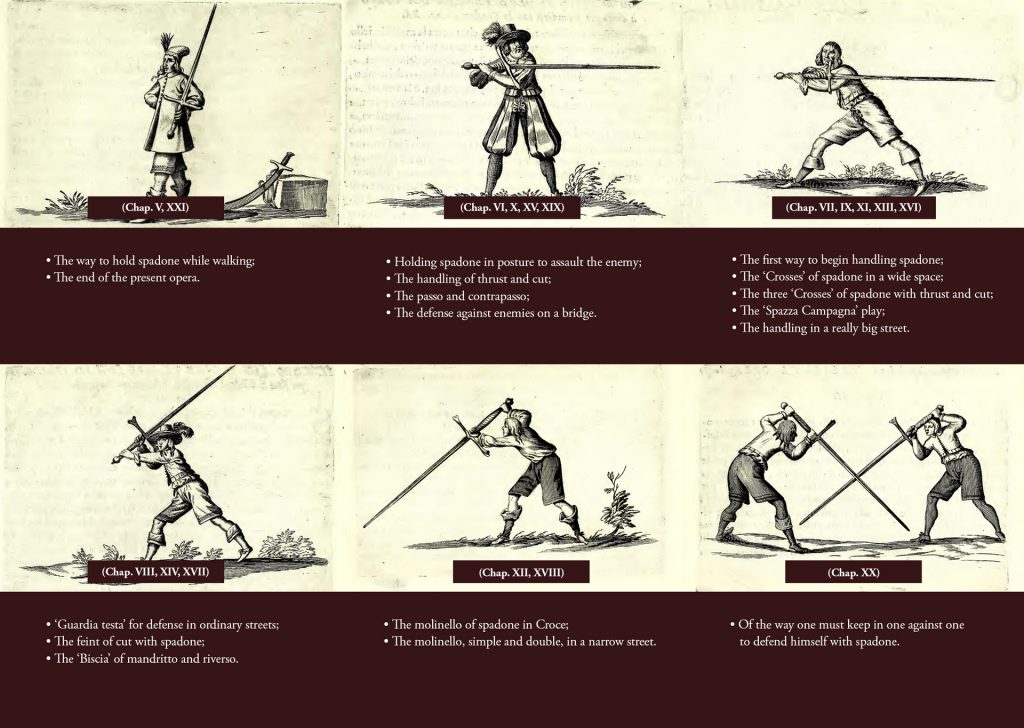

The book is illustrated by 16 prints (although they provides only six subjects as five of them are repeated more than one time); the illustrated chapters never have more than one print. It is important to note that this is the only known treatise providing images of fencers using spadone to perform non-duel techniques.

The content inside the main chapters is a collection of teachings that I divide in two categories (general handling and specific plays) summed up as follow:

General handling

- The cuts (the first way to begin handling spadone)

- The handling of thrust and cut

- The molinello of spadone in Croce (here the term Croce, cross, is not clear if referred to the same Crosses he mentions afterward*)

- The feint of cut with spadone

- The passo and contrapasso (step and counterstep)

Specific plays

- ‘Guardia testa’ (head guard) for defense in ordinary streets

- The ‘Crosses’* of spadone in a wide space

- The ‘Crosses’ of spadone with thrust and cut

- The ‘Spazza Campagna’ (countryside sweeping) play

- The handling in a really big street

- The ‘Biscia’ (little snake) of mandritto and riverso

- The molinello, simple and double, in a narrow street

- The defense against enemies on a bridge

- The defense against another spadone

Every chapter has its single notion and all of them are presented with no specific distinction, but not in the order I give here that is useful just to divide the techniques.

The comparison with the Iberian masters

The first and significant difference between Alfieri and masters such as Godinho and Figueyredo is that Francesco actually published his work on spadone: his treatise is a book, while the two cited Iberian sources on montante are manuscripts of which we have no real clue about the final destination that should have been. Were they meant for future publishing? Were they just ready to use personal notes for practical application? Probably we will never know. Of course, similar difference can be set with other shorter Iberic old sources that, all of them, notes and handwritten excerpts.

This first difference is probably the cause of the second: Iberians are very strict and repetitive in their exposition, explaining just what is necessary to perform the regra correctly, step by step, while Alfieri prefers an annoying verbose prose that waists many words to say not too much actually.

Alfieri’s spadone resembles Esgrima Vulgar masters teaching approach: he works with rigid given techniques rather than general fencing principles to apply in a dynamic way, unlike the Iberian Verdadera Destreza phylosophy, which was born in the beginning of XVII century. He gives us situations and specific movements to adopt to face them (wide street, narrow street, wide space are all familiar to the Iberians as well), though he seems to be superficial and this is not always his unique method.

Particular teachings such as molinello, feints, passo and contrapasso are more similar to generic basics that can find their place inside more complex actions. For Alfieri, these are just lessons to be learned, divided in chapters, but not specifically to be intended as given sequence of actions like Iberic regras, where some basics like these are present too but offered implicitly, always hidden inside a chain of linked actions nonetheless.

Study and interpretation issues

Alfieri is not a good master to start from when you are approaching spadone; apart from the language (though you can find an English translation inside ‘The Art of the Two-Handed Sword’ by Ken Mondschein), the nature itself of the teaching is far from easy understanding. Alfieri does not indulge in details: he has less than half of Figueyredo’s contents and he does not possess Godinho’s prolix descriptive step by step approach. The result is a somehow vague source that leaves space to suppositions and assumptions rather then strong convinctions.

Alfieri’s annoying conversational prose makes it difficult to deduce how he is asking us to perform his teachings; techniques such as molinello are not described in details and the way to cut with mandritto and riverso many times is too general, as well as the correct spatial stepping for misterious techniques like Biscia.

Sometimes the impression is that he is just using the book as a mere reminder for someone who has attended one of his lesson in person, and in chapter VIII, talking about its illustration, he states that the ‘figure will help you to awaken the memory, may be the case that for length of time, and little use, my memories given to you by voice had gone out of your mind’.

All of this makes the treatise a possible secondary source to enrich your knowledge, or to find new interpretations, links or theories, but you can hardly count on it as primary content upon which building your study. Better to say: you don’t have any actual logic reason to, having the possibility to pick up one among the Iberians. I hope to prove me wrong with further time and study, but the apparent lack of researchers focusing on Alfieri could be a sign of this difficulty.

The only hemaist, of which I am aware of, who has tried to give a succesful free to share interpretation of his teachings is the well praised James Clark from ‘Capital Kunst des Fechtens’ (Alexandria, near Washington, Virginia). You can check his Youtube video here. At the moment this is the only material I know and that I would suggest to start from (but please, send sources to other material you are aware of, if you have).

A treatise filled with oddities

Apart from its criptic prose, the treatise is full of weirdness that puts it inside the annoying side of the ‘interpretation spectrum’ and weakens Alfieri’s credibility, but let’s go through them one by one.

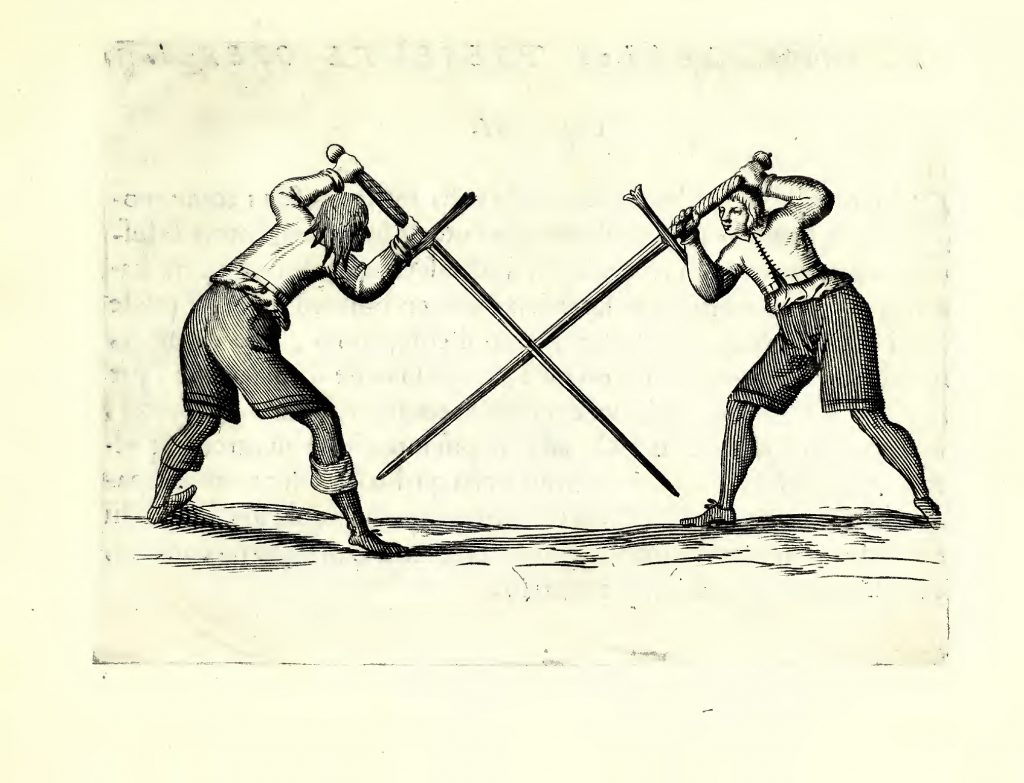

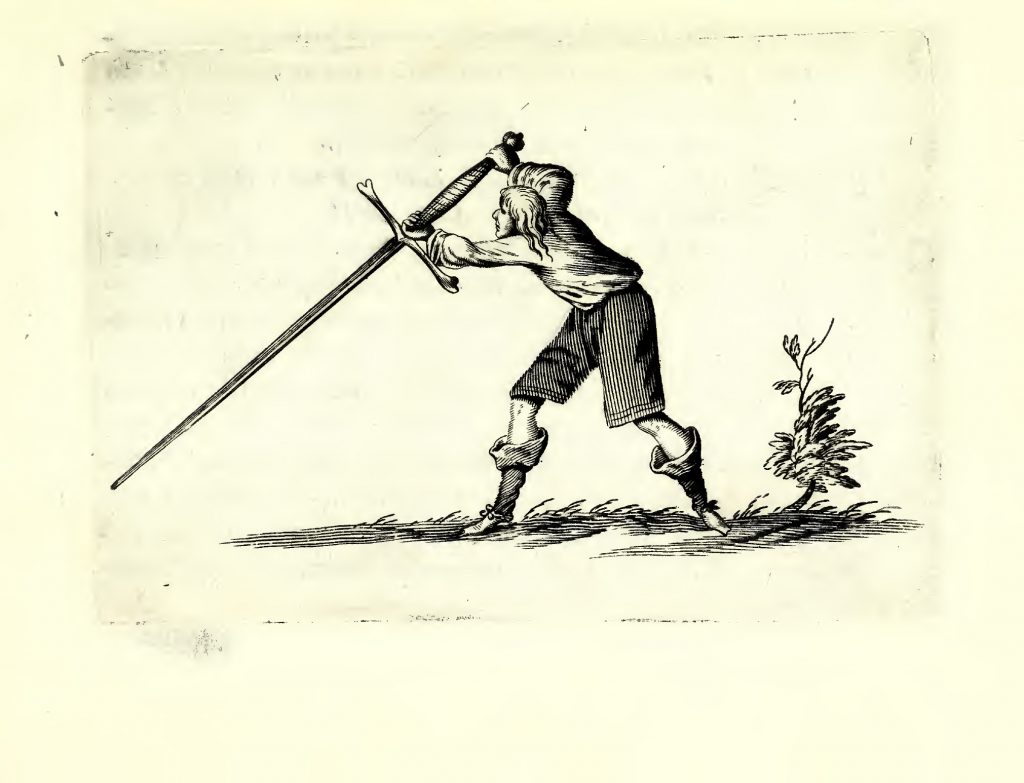

He completes most of the chapters with an image but almost all the time – if not every time – the images are not of real help. With exception of chapter XX, the prints show only the spadone fighter and give us no clue on the context nor on his enemies; we don’t know how he is moving around and how he is playing his cuts. We do not know what he is doing actually and in the text there is no evident description relating to the poses shown in the images. This is not a problem per se, I mean, we can go along with Iberian sources that have no prints at all, but the idea of having almost useless pictures is discouraging.

Chapter number XX print clearly shows two fighters facing, helding the spadone with the right hand turned, with the thumb tip facing the pommel and not the blade which to my knowledge is not something we can find in any other fencing source dedicated to this weapon.

Chapter XII and XVIII prints show the fencer performing molinello, but the hands have swapped position: the right one on the pommel. Again: unless you are left handed, this is something weird.

Another general fact about the prints, like I say above, is that they recur many times: the same exact pictures are offered to the reader to complement techniques that, when described by words, appear different. Dear Alfieri, didn’t you have money to pay for more prints?

Two separate chapters are named XVII due to a typographic error, while the second one should be XVIII.

Many other things could be said about Francesco Alfieri but this presentation has a good overview and right now is just long enough, so what has been left behind could be material for a future examination.

If you liked this article and you are willing to read further contents about Italian spadone, Iberian montante and other big swords you can follow The Spadone Project Facebook page putting a Like to it. Thank you!

Hi and thanks for sharing your work.

Just a quick note (with no further thinking behind it): you wrote “Chapter number XX print clearly shows two fighters facing, helding the spadone with the right hand turned, with the thumb tip facing the pommel and not the blade which to my knowledge is not something we can find in any other fencing source dedicated to this weapon.”

There is indeed another one (and you’ve surely seen it): it’s Achille Marozzo’s “guardia contra armi inhastate”. The right hand is placed on the ricasso between the crossguard and the langets instead of on the grip, but due to its position very close to the crossguard, I would say that it’s far more similar to Alfieri’s guard than to a halfswording technique (in fact, Marozzo’s grip seems to be shorter than Alfieri’s, so the distance between the hands looks actually more or less the same).

I think it’s interesting to note that both Marozzo and Alfieri suggest to use this grip against long weapons.

Some of the staff and polearm guards (in Meyer, Mair and I guess many others) are also similar, although of course it’s not spadone.