In this new article for Mamma mia, spadone! I’m going to discuss what we know so far about the use of spadone in sea fight during XVI century. I will try to leave apart excessive speculation, going straight to the sources in order to provide you a clear list of episode from which we can get to some conclusion.

I was able to collect just a little number of sources that witnesses the past of spadone among sea fighters, but nonetheless the number of episodes is enough – and so widespread during XVI century – to be considered, if not a proper truth of fact, at least an exciting heroic topos praised by many authors of the time.

A galley weaponry according to Pantero Pantera

Pantero Pantera (1568-1625) was born in Como, member of a family of merchants and enlisted for the Pope’s fleet in 1588, some years after the father’s death. After years of career under the pontifical naval forces he wrote the book L’Armata Navale (1614), that provides us with a really exhaustive list of equipments – both weapons and other utilities – that were supposed to find place on board of a galley (for a matter of brevity I will leave it out of the article). This book is considered to be the first Italian publishing dedicated entirely to naval warfare.

Among a rich collection of weapons, in terms of kind and quantity, we find only two spadoni (page 176). The difference between this pair and the quantity of other weapons listed is a first sign that, maybe, tells us that this kind of weapon was actually used but only as a really specialistic one, reserved to a few soldiers and perhaps only in particular circumstances. Just to make an example: every ship should have carried 50 swords without considering those carried by the soldiers by their belts (Pantera underlines personally this distinction). So we have a ratio of 1 spadone every 25 swords, at least. To make it even more clear (while knowing that only two reports about a battle can’t be taken as a unique truth), Giovanni Pietro Contarini in Historia delle cose svccesse Dal Principio della Guerra mossa da Selim ottomano a’ venetiani […] (1572) and Francesco Sansovino – who quite surely read Contarini’s book – in Historia universale dell’origine, et imperio de’ turchi (1582), report almost the same exact words about Lepanto Christian fleet: «[…] being for each galley men with sword two hundreds, and on the Captain galleys, and on those of fanò (A/N a particular kind of galley), according to the rank, where three hundreds, and where four hundreds […]». We can approximate 1 spadone every 100 men for the smaller ships, perhaps something more, if we suppose that someone among the soldiers had a spadone of his own, out of the ordinary galley board equipment. An almost marginal weapon it would seem.

Pantera’s book provides us with no further notes about the reasons and use linked to their presence on board: a given speculation is that one was hosted on the prow and another on the stern, ready to be used to wipe out the enemies from one end of the ship to the other in critic situations (Note: this hypothesis is not mine and comes from the web, but I can’t remember where I read it, so forgive my memory).

Note: a special mention to Moreno dei Ricci who first mentioned Pantera’s book in an article for the Italian History blog Zhistorica and from which I was able to discover it.

The battle of Lepanto (1571)

Lepanto probably is the most known sea battle of the Renaissance – fought by the Holy League against the Ottoman fleet – and for which we have some interesting accounts just due to its relevance in terms of dimension of the event. Once again, Contarini has left us some words just one year after the battle, printed in 1572 but probably written really close to the actual event. He describes the moment in which the Christian fleet suddenly got a line of sight to the Ottoman ships, «the same Sunday at two hour of the day», surpassing the Curzolari reef. The «cheerful Christians» began to prepare their ships, cleaning the decks and distributing the weapons «all with the relevant weapons to them» that counted: «arquebuses, halberds, iron maces, pikes, swords, and spadoni». All «distributed among sbarre, balestriere, pupa, proua, & meza galea» (A/N all parts of the galley).

Contarini describes the battle as well and here we have a short excerpt framing that terrible carnage: «Three galleys had closed together to four, four to six, and six to one of the enemy ones as well as of the Christian ones all of them fighting very cruelly not to leave life to each other, and they had boarded many galleys of this and of that side, Turks and Christians, fighting together tighten to battle with the short weapons, from which few left alive, and without end was the mortality coming out from spadoni, scimitars, iron maces, cortelle (A/N probably weapons like Messer), manarini (A/N little cleavers), swords, arrows, arquebuses, and fireworks, in addition to those that misfired for different accidents, retreating, throwing themselves, drowned in the sea, which was already thick and red in blood.» As you can read, spadone appears among a moltitude of other weapons.

Spadone is mentioned as well by Friar Gasparo Bugati, inside L’aggiunta dell’historia universale, et delle cose di milano (1587). Bugati has left us a quite dramatic description of that day that I find particularly impressive, personally. You are going to feel some similarities with Contarini. More than ten years had passed and it is possible that part of the narration behind Lepanto had developed into an epic elaboration, reproduced by authors following a common path. Bugati’s description, apart from the hellish portrait of the battle, is interesting because by the time he wrote, apparently, the notion of spadoni as deadly weapons during Lepanto had become common. He wrote:

«And everything already made bloody for the terrible and wonderful mortality that was in that day all cluttered in stinky, thick and dark smoke, quite darker than night; very confused day of uncountable voices, cries, screeches, clamors, and thunders: and all the galleys were meshed and already tangled together: and the Reali to the front and to the irons (A/N Reali are ships but can’t say what the sentence means exactly though): when everywhere soldiers, standard bearers, and captains were jumping now on one and now on another galley; and overwhelming, and pressing, pushing, and going forward, someone with swords, or spadoni (under which fell many many Turks) with scimitar, maces, halberds, and pikes: throwing balls, pignatte (A/N some kind of bomb I guess), and diabolic new fire trumpets, going on the uproar of cannons, and the arquebuses storm between Spaniards, and Spachi (A/N a Turks knights order); between Italians, and Janissaries, between Germans, and Turks, and between venturers and venturers: and even between Christians, and Christians, and between Turks, and Turks, due to the too thick darkness of the smokes that blinded the Sun, and the daylight, as well as the eyes of the fighters: though distinguishing our vessels from the adversaries only by the fireworks, the Turks having none if not few, and of common appearance: in such a way that everywhere there was an image of Death, and a drawing of Hell.»

But let’s discover who were some of those valiant warriors who faced the Turks handling these two handed swords. Lepanto counts at least other four reports, about valorous fighters who proved their skill with spadone. The references come from four different books published years after the battle: ten years, seventeen years, twenty years and thirty six years afterward (the pass of time and the absence of recorded direct eye witnesses are two element to keep in mind).

Antonio Canale

The oldest source is Historie del Mondo (1581) by Mambrino Roseo da Fabriano who tells the story of Antonio Canale, a Venetian Proueditore (a kind of administrator and commander) who, despite being already fifty years old, slaughtered many enemies with a spadone a due mani, boarding the Turkish galleys to claim back a ship taken by the Ottomans during the battle. Mambrino tells us that Antonio put a pair of cord shoes not to slip on the deck and, not to be forced inside a heavy metal armor, he wore a uesta, a vest/dress, to secure himself from the arrows. Nothing more is said about this episode, but we can guess by some of the author’s words that Antonio was able to board more than one enemy ship, even though we can’t tell if the man was alone or followed by his soldiers. The reported fact did not get lost and probably many years later (thirty three) the book was read by Pantero Pantera who put the same tale inside his aforementioned L’Armata Navale, using similar words, and suggesting to provide the ships with more of these weapons due to their valuable use in the past. Ten years had passed and, even considering Mambrino’s account as an exaggeration, once again – 1572 – that good man Contarini reported: «Marco quirini & Antonio Canale both of them will remain eternally illustrious to the world for their glorious facts in all of this war, besides the extermination done to the enemies during the Day.» a mention that we can’t exclude to refer partially to this same spadone fight (if you want to read the complete translation of Antonio Canale’s original excerpt by Mambrino Roseo you can check this old post of mine).

Giacomo Trissino

According to Giacomo Marzari in his La historia di Vicenza (1591), another hero of Lepanto has been Giacomo Trissino. Giacomo was a young man and a gouernatore (a governor) of a galley of the Venetian Republic but unfortunately, unlike Antonio Canale, he did not make it out alive from the battle, as he was shot by a falconet; «a holy Death without doubt» as Marzari wrote. According to the author, it was a death to be desired by any honorable knight. The source tells no other details of real relevance as it is just a short written funeral memorial but, for the complete translation, again, you can check here.

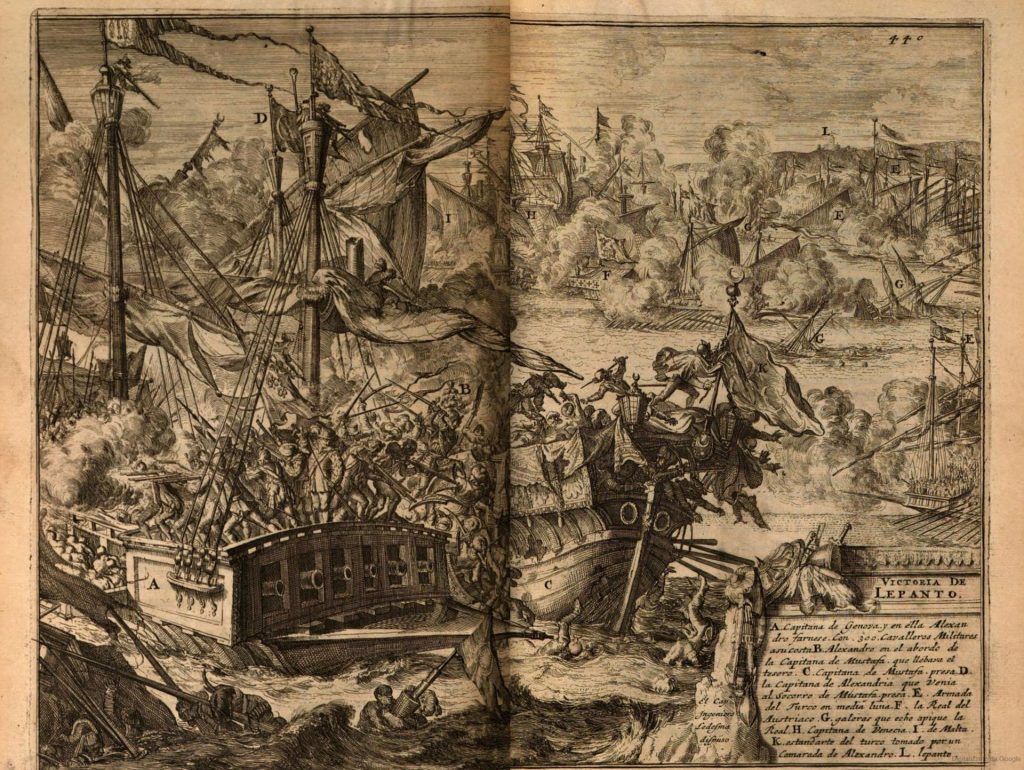

Alessandro Farnese

The third account involves a much known and famous figure of the Italian Renaissance: Alessandro Farnese, important general under the service of Spain and third duke of Parma and Piacenza (near to my city Reggio Emilia). A first mention can be found in Giovanni Botero’s I capitani (1607), thirty six years after the battle, while a second one came much later inside Della guerra di Fiandra by Famiano Strada, first written in Latin and then translated into Italian by Carlo Papini (1639) and into Spanish by Melchor de Notar (1681). Side note: the original term is grandi gladio (big sword) then spadone used by Papini and at last translated into montante by Notar.

Botero tells us that Alessandro jumped from his galley to assault the enemy one with a spadone a due mani with much risk to fall dead as the Turks tried to hit him to the legs, being him well armored (armored with the classic infantry corselet with no leg protection I guess). Alessandro, playing the spadone in a circle, mistreated many enemies and then was followed by his men and together they took the Turk galley (for my complete translation of the Spanish version go here).

Strada’s version adds some more details: the author says about Alessandro that spadone was a weapon that he accustomed himself to handle excellently and that he jumped furiously on the galley opening the way to his men. They nearly forced the galley survivors to surrender if not for a new Turkish galley reinforcement; the fight went on but, due to another supporting ship, Alessandro was able to defeat the Turks, conquering both the enemy ships and finding with surprise the big amount of money that one of them was carrying.

Father San Francesco

The accounts comes again from Gasparo Bugati’s book. The story is short so let’s put it shortly.

San Francesco was a friar of the Cappuccini order, embarked on Reale (A/N the name of the ship or perhaps a Royal ship) and put there to exhort the Christian militia to fight for the Faith. When the situation got worse, after getting a wound (we don’t know how) and seeing the Turks boarding the ship, he decided to help in a more proper way. Bugati writes that in that moment even his General was fighting. San Francesco, «lost his usual patience» left the cross he was toting and took a «spadone to defend his skin and he performed very well». Interestingly, this is not the only source we have about a Church man fighting with a two handed sword, but it is not matter for this article.

The siege of Koroni (1532-1534)

Another sea clash involving spadone is the siege of Koroni, in Greece. Koroni had been under Venice control since XIII century and then was captured by the Ottomans in 1500. In 1532, Charles V – new ally of Genoa since 1528 – asked admiral Andrea Doria to attack the Greek city as a diversion, during the Habsburg-Ottoman wars in Hungary (1526-1568). Doria did it and conquered the city that was then sieged again by sixty Ottomans galleys in 1533 to claim it back. This tale takes place during this second sea siege.

One account comes from Marco Guazzo in his Historie di tvtti i fatti degni di memoria from a further printing of 1544 but is mentioned as well inside Supplementum supplementi (1553), a chronicle by Giacomo Filippo Foresti, who probably took the story from Guazzo’s version, as the two paragraph have many linguistic similarities.

Captain Nermosilia

This time, the hero is captain Nermosilia who, protected by his corselet and other pieces of armor, almost led to freedom a ship taken by the enemies. Followed by his soldiers, Nermosilia made a mess, crashing legs, arms and heads with his «spadone a due mani». We don’t know much more: after the first ship they were able to help a second one fallen into the same condition. Guazzo says that «for the vigor of his followers», the ship was set free, so this time apparently it was possible due to a group effort, or the author admits it more honestly than the others. You can find my complete translation of the original excerpt by Marco Guazzo here (even though from the 1546 book reprint, which has the same words after all).

The Portuguese in India (probably before 1525)

This adventure is collected inside Fernão Lopes de Castanheda’s sixth book of História do Descobrimento e Conquista da Índia pelos Portugueses (1554 according to Spanish Wikipedia) which I analyzed in one of his many translations; the specific one is Italian (1577), though by a Spanish translator, Alfonso Ulloa. The adventure involves Andrea di Britto’s brother whose name did not survive to make it into the chronicles. Andrea supposedly was a Portuguese adventurer of some kind, under order of Jorge de Alboquerque, governor of Malacca (a city in today Malaysia) and Cochin (a city in today Kerala, a State in India) during the decades of Portuguese exploration around Asia, between the end of XV century and the beginning of XVI century.

Andrea di Britto’s unknown brother

Andrea went from India to Malacca with an expedition of 60 men circa. He then, passing from a place called Sian, went to Pam to collect supplying, bringing with him twelve Portuguese. Once in Pam, the king of that territory attacked them in the morning. The attackers were Moors as in that territory in that time they were occupying some areas. The Moors were «without number» and were fighting with fresh men as they could replace those too tired to keep fighting, while the Portuguese could not and began to die. All the Portuguese succumbed even though they had fought running with «marvelous speed» everywhere was needed on the ship. The last survivor was Andrea di Britto’s brother (the author tells he did not know his name) who fought with a two handed sword and that was considered a devil due to his valor: he wiped the ship for two times. Then, weakened by the fight and not to be captured, he tied two falconet burst chambers to his feet and he threw himself into the sea, drowning. Then the ship was captured and afterward the facts were told by an interpreter who made it out alive because he was of that land and was able to reach Malacca.

There is no date for these facts (I was not able to trace it so far). Even though, knowing by the book that they took place when Jorge de Albuquerque – governor of Malacca and Cochin – was still alive, we can put them before 1525, the reported year of his death (as stated by Enciclopedia Treccani online).

The presence of the word spada da due mani instead of spadone could be a hint for this dating, as spadone usually is used to translate montante, but this word begins to appear later (probably around 1570 more or less), while originally till the first decades of XVI century it was still espada de dos manos (like witnesses Barbarán and other early sources). It is possible that Fernão Lopes wrote the excerpt from an older source, dating back to the time before montante became a common word, and he left it as it was. Possible because at least twenty nine years divide the fact from the date of publishing, and Lopes must have found that story somewhere. Then Ulloa, Spaniard by origin and so well suited to translate his language into Italian, opted for spada da due mani, the perfect form for it.

Given the years, that of Cochin, could be intended as the oldest report of a two handed sword sea fight that I have knowledge of, so far. The ancestor of all the glorious fight to come in the years afterward.

You can find my complete translation of the original excerpt here.

The exaggeration of these accounts

The stories have similarities and the impression that could strike us is that of a topos, a narrative figure that can’t be missing in a good sea fight tale; something that embodies the spirit of a relentless and just warrior. With little variation, it is quite like a script: the battle is raging, the ship is falling under the pressure of the enemy, but suddenly comes the hero, maybe clad in armor and surely toting a fearsome spadone with which all the foes are defeated and the ship is set free. Sometimes the just hero gives his life while trying the impossible.

We should not forget that during XVI century the way communications spread was different from what has been after the invention of the most modern devices for mass information and there is evidence of fake news even during past centuries. In this particular case (as well as in many other we will face inside Mamma mia, spadone!) just the fact that many accounts are reported many years after the actual events should make us careful in taking for accurate – or real – everything we read on those old pages. Even more, considering that we are dealing with short excerpts that often tell about battles and situations of probable great confusion and disorder, where the original first eye witness is 99% case unknown.

When the story comes from adventurers involved in journey far away from home, like the reports from the Portuguese conquests and explorations we can catch only a glimpse of what could have been actually. Hundreds of miles away from their nation, among people not talking their language and sailing seas of wild lands with nothing but a few witnesses among them, how can we always discard the possibility of made up stories and exaggerations? How much did the story travel before to be put inside the book? How many mouths did tell the story before it arrived to the author? It is indeed a huge reconstruction maze.

Propaganda and praising reasons were there as well: most of the time, when personal profit and interests are involved (mostly in case of war, kingdoms and politic), for a book – or any kind of communication device – is unlikely to preserve a neutral point of view without letting go to self celebration (being it referred to a commander, a nation, a population…), when its aim is to tell victorious or exotic and adventurous events to a whole nation or continent. Consider that, in XVI and XVII century, many books were dedicated to kings, emperors, popes and other European nobility figures, sometimes even published inside royal printings, so we should not discard some censorship action or storytelling boost.

All of this doesn’t mean we should always consider them fake but we should take these stories with a grain of salt, and at least talking not about what happened, but about what happened according to what a book tells us. It is a subtle difference, I agree, but an important one.

The Iberian regras to fight on a galley

We don’t have much about the techniques used to fight on ships with spadone; probably we can assume that, apart from possible narrow spaces, there was no much difference compared to a fight on the ground. The dimension of the ship, the wideness of the deck and the number of men on it of course had an impact on the fighter’s possibilities of performance, as well as the presence of one or more masts but not in a way particularly different from the restrictions of narrow streets or of other crowded places.

We know just three way to fight specifically meant for battles on ship: two montante regras by Diogo Gomes de Figueyredo (1651) and one regra by Domingo Luis Godinho (1599). Godinho expresses his teaching in a way – and during a historical period – that leaves space to stronger belief that it was actually meant for this, while Figueyredo’s regras could be seen just as exercises. I say this because is the master himself – in the last paragraph of his notes – telling the reader that his regras are not techniques to be put on effect just in a brainless way, but as a pool of options we can mix from every regra just to fit our specific need and so, exercises for a more complicated handling. In this sense, Coxia de galee, in its simple and composed variations, could be just a drill with an exotic name, even though, it actually has some interesting features that make me think that it has at least roots in a real application.

Godinho works only with thrusts, while Figueyredo mixes some thrusts with more prominent horizontal cuts. They both works on fighting on two opposite directions. In the case of Figueyredo, the stepping does not follow the general criteria he adopts for the majority of his drills and could be seen as more stable, possibly to balance the ship rocking. The horizontal cuts could be a necessity to swing the blade over the heads of other soldiers or rowers that usually crowded the ships, probably staying on a lower level of the deck. Some galleys had a really narrow gangway running in the center of the ship, from prow to stern, sometimes enclosed by two handrails all along the length, so horizontal cuts could be used to avoid getting stuck on wood with the blade while attacking; thing much more possible with vertical cuts.

Considering the length of the article, I think I will come again to fencing techniques later, to further expand them. This is quite all we know so far about two handed sword use at sea. I hope not to have bored you too much: the article was actually pretty long, but I think this is just the right way to be exhaustive and informative about the topic.

If you liked this article you can share it! And if you are willing to read further contents about Italian spadone, Iberian montante and other big swords you can follow The Spadone Project Facebook page putting a Like to it. You will choose the next topic, taking part to my future survey. Thank you!

Sources

- Alfonso Ulloa (translated from Fernando Lopes di Castagneda’s Portuguese version), Historia dell’indie orientali, Venice 1577

- Diogo Gomes de Figueyredo, Memorial da prattica do montante, (MS) 1651

- Enciclopedia Treccani Online [Alfonso de Ulloa]

- Enciclopedia Treccani Online [Antonio Canale, o Canal]

- Enciclopedia Treccani [Jorge de Albuquerque]

- Enciclopedia Treccani Online [Pantera Pantero]

- Famiano Strada, De bello belgico decas prima, Antwerp 1635

- Famiano Strada (translated by Carlo Papini), Della guerra di Fiandra Deca Prima, Rome 1639

- Famiano Strada (translated by Melchor de Notar), Primera decada de las Guerras de Flandes, Köln 1681

- Francesco Sansovino, Historia universale dell’origine, et imperio de’ turchi, Venice 1582

- Gasparo Bugati, L’aggiunta dell’historia universale, et delle cose di milano, Milan 1587

- Giacomo Filippo Foresti, Supplementum supplementi delle croniche del Venerando Padre Frate Iacobo Philippo,Venice 1553

- Giacomo Marzari, La historia di Vicenza del Sig. Giacomo Marzari fu del Sig. Gio. Pietro Nobile Vicentino,Venice 1591

- Giovanni Botero, I capitani del signor Giovanni Bottero benese, Turin 1607

- Giovanni Pietro Contarini, Historia delle cose svccesse Dal Principio della Guerra mossa da Selim ottomano a’ venetiani, Venice 1572

- Luis Godinho, Arte de esgrima, (MS) 1599

- M. Mambrino Roseo da Fabriano, Supplemento overo Quinto volume delle Historie del Mondo, Venice 1581

- Marco Guazzo, Historie di tutte le cose degne di memoria quai dell’anno 1524 fino questo presente, Venice 1544

- Pantera Pantero, L’Armata navale, Rome 1614

- Wikipedia [Andrea Doria]

- Wikipedia [Fernão Lopes de Castanheda] and [Spanish page]

- Wikipedia [Habsburg-Ottoman wars in Hungary]

- Wikipedia [The battle of Lepanto]

- Wikipedia [The siege of Koroni]